|

|

|

|

|

The Mystical Consistency of Matter

Magnus Thorø Clausen

|

| |

|

| | |

|

"Can you understand,’ asked my father, ‘the deep meaning of that weakness, that passion for coloured tissue, for papier mâché, for distemper, for oakum and sawdust? This is,’ he continued with a pained smile, ‘the proof of our love for matter as such, for its fluffiness or porosity, for its unique mystical consistency. Demiurge, that great master and artist, made matter invisible, made it disappear under the surface of life. We, on the contrary, love its creaking, its resistance, its clumsiness. We like to see behind each gesture, behind each move, its inertia, its heavy effort, its bear-like awkwardness."

Bruno Schulz: Traktat o manekinach [Treatise on Tailors’ Dummies or the Second Book of Genesis],

|

| |

|

| | |

|

Etymologically speaking, the word "text" stems from the Latin, textus, which refers in turn to weaving. What this indicates is that writing was originally more closely connected to weaving or knitting than we might imagine in the present day. Viewed from a comfortable distance, however, there are also obvious similarities between these activities. In each case, we are dealing with joining or interweaving strokes or strands into larger interconnected entities. In terms of the visual aspect, there’s not a vast difference between a rectangular piece of textile and a rectangular text and certainly not in the eyes of somebody who has not learned to read. As it was not until around the middle of the nineteenth century that the literate percentage of the population expanded into a majority, there have been – historically speaking – rich possibilities for sustaining an open connection between the text and the thread as interwoven surfaces.

|

| |

|

| | |

|

The coupling between text and textiles, however, immediately becomes outmoded when we start talking about meaning. Texts can be read: they have a specifically concrete content and they are evidently sign-bearing while knitted and woven surfaces, on the contrary, make their appearance as primarily sensual phenomena that are empty of meaning. Of course, a carpet or a rug can be interpreted in terms of its historical, social, cultural and economic implications, in much the manner of a text or any other object in the world, for that matter. But if we focus on the way the carpet has been woven or on how one thread weaves its way between the front side and the backside of the rug, the meaning – or significance – becomes outmoded. On this level, it is only the physical differences that capture our attention. On the other hand, perhaps this manner of dividing things up is not all that absolute. Here, it would be obvious to point toward the art of sculpture as being one of the realms where these two areas of activity have always been situated in a more or less open exchange with each other. A convincingly represented fold in the marble’s surface or a welding between two iron rods reaches incessantly from physical space further across and into an immaterial or mental space. The reading of sculpture might fundamentally consist of an attempt to conjoin physical material with the conceptions and experiences with which one enters into the meeting, fully aware that they never hold water. What this can entail in the best instances is that the viewer is moved to another place than he or she was standing beforehand: closer to the material which is, after all, the fixed point of rotation and the fixed terminal point, until the next time he or she stands in front of the work and tries to see whether it is possible to progress a little bit further.

|

| |

|

| | |

|

Even though sculpture’s transport between material and thought can, principally speaking, be regarded as being applicable also to sculpture created before the era of modernity, the relation and perhaps even more especially the awareness of this relation are primarily bound up with aspects of sculpture created in the period after 1960, a moment in time when the focus has been specifically aimed at the material and its potentials for meaning. The American sculptor, Robert Smithson, was one of the people who, during this period, spoke explicitly about sculpture as a unity of matter and mind, in what he designates as an interminable material dialectics, where language comes to be just as primary as steel (or thread, for that matter). If we go back to our examination of rugs and textiles, which is the focus I am trying to maintain here, the question becomes how these materials, on the physical plane – in their manner of being woven and in their spatial placement, for example – can achieve this opening out toward conscious awareness and thought. This can operate as a possible line of approach to Martin Erik Andersen’s work, where rugs, textiles and threads have been fundamental elements since the beginning of the 1990s. It is, naturally, somewhat artificial to focus exclusively on textiles and rugs since, in the actual art works, they do in fact often converge with a number of other materials. However, my hope is that, in taking this as a point of departure, the more narrow focus can and will open up for a more precise specification of certain broader thematics. In this connection, I have chosen to split up the present review into three general headings that can serve respectively to indicate three regions with which the material work conjoins itself and explores: the body, the drawing/writing and the ornamentation. This could also be apprehended as suggesting a chronological movement from the past to the present; however, it would not be entirely correct to draw such a trajectory. On the contrary, it could be said that the works actively operate counter to such a delimitation and draining in the way that they are incessantly laying down trails and piling references on top of each other in a constant condensation that continues from one artwork to the next. The output, regarded as a whole, assumes the character of an open processual space, where all elements and meanings can be recapitulated somewhere else in a different material context. For the spectator, this offers the sensation of finding himself/herself standing on the edge of a circle, whose center is constantly being displaced further and further away from the tangible space where one happens to be standing. The sculptures balance between being emphatically physically present and, at the same time, on their way toward erasing themselves, right up to the limit where they are almost disappearing from view; or, in any event, where they are vanishing from whatever thought can hold onto with its notions and conceptions.

|

| |

|

| | |

|

| | |

|

The Body

|

| |

|

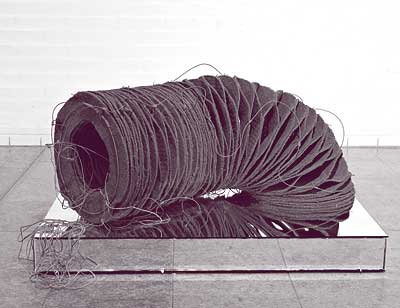

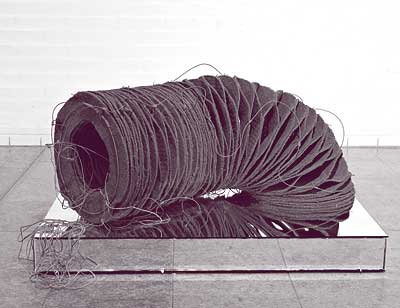

Cotillon / Nervenanhang [Cottilion/Nervenanhang] (1992) is an accordion-like object that has been sewn together from rounded cut-out pieces of felt and placed directly on the floor. What is significant about this piece is that it can exist in several positions. In the folded-together state, it manifests itself most distinctly as some kind of enigmatic and opaque receptacle. However, when you pick up the cords that have been fastened to the sides, the object folds out into a more open and transparent vertical structure. As indicated by its title, the prototype for this piece is a cotillion, which is a small and colored ornamental object of Eastern origins which one might encounter at a party, at a carnival or in an amusement park. Here, the ornamental object has undergone a number of fundamental displacements: the paper has been transformed into rugs, the colorful hues have been replaced by a dark red nuance (the list of materials specifies this as lead-colored minium) and the object has been repositioned from the ceiling to the floor. The most crucial displacement, however, is the change in scale. No longer does the object function exclusively as a decorative eye-catcher. Instead, it has become converted into a body-like volume that, in its unfolded state, actually juts a little ways above the viewer’s own body. The use of carpet as material plays an important role here, since the carpet in itself is very directly related to the body and to the feet. Would it be stretching perceptions too far, similarly, to regard the reddish color as a reference to the body, for example, to archaic body paintings? In any event, the object elicits the effect – with help from the carpet’s tactile associations – of inscribing the body into an otherwise visual interpretive context. The second part of the title, “Nervenanhang” or nerve attachment, stands very open. Perhaps it can be used as a jumping-off point for a more somber frame of interpretation, where the object becomes some kind of translated nerve for the registration of pain? Should we hesitate about carrying things this far, perhaps we also could merely apprehend the nerve association as yet another kind of superimposition into the cross field situated between the bodily and the mental spaces, around which the work circles.

|

| |

|

| | |

|

|

| |

|

Cotillon / Nervenanhang [Cottilion/Nervenanhang] (1992/2008)

|

| |

|

| | |

|

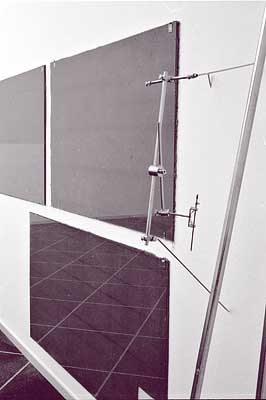

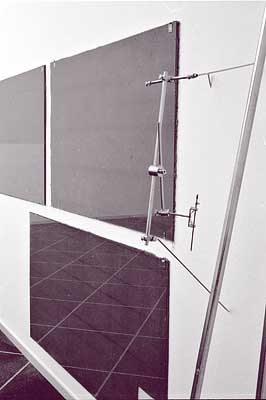

Another sculpture that makes use of carpet material as a potential model of the body is a work entitled 3 Poles (1996). This piece consists of three rectangular surfaces of glass that have been mounted onto the wall. When you move up closely, you can see that layers of felt have been inserted between the glass plates and the wall. The effect that this elicits is that in the act of contemplation, one attains a dual material consciousness. On the one hand, you are being reflected by the pane of glass, which moreover is oriented toward the surrounding room. But at the same time, the gaze is held in check by the dense and undifferentiated felt mass, which functions as some kind of impenetrable body on the other side of the glass. Consequently, the sculpture situates itself in the transition between visibility and blindness, where the act of looking into the work of art similarly implies the act of looking into a bodily mass of rug material, which blocks the sight. In a broader sense, this threshold region has actually also traditionally been a habitat for sculpture, which has always had an unsettled relationship to the purely pictorial appearance. For example, the sculpture can be separated from the painting’s definition by virtue of physically possessing a backside that is not accessible until one moves his or her own body around the object. In addition to the glass and the felt, the sculpture contains three freestanding steel pipes, which conjoin the wall with the floor as well as a pointing machine, which has traditionally been used for copying physical forms in an exact way. Like the glass panes, these elements circle around reflection and reduplication, even though they have been displaced from the body and transposed into the architectonic space. The pointing machine’s three copying points are placed in toward the wall while the steel pipes’ end points translate the points of a triangle from the floor to the wall. However, in spite of the displacement that is facing the space, what is secured here is an interest in the region between visibility and blindness. Among other things, our fascination is connected with the fact that both the steel rods’ and the pointing machine’s copying depend on physical contact rather than on visual registration.

|

| |

|

| | |

|

|

| |

|

3 Poles (1996)

|

| |

|

| | |

|

In the former piece, the use of the carpet transpires in the context of a direct albeit openly illustrative schematization of the body, while what we have in the latter instance is a schematization that moves around figurative pictoriality and into a tactile and partly architectonic space. Notwithstanding this rather dramatic disparity in the respective approaches to the body, both of these sculptures are oriented around a way of delicately shading the visual reading of the physical space and raising issues concerning that reading. By way of alternative, a somewhat more cloudy situation is being sketched out where the visual aspect, in different ways, has been wound up within a tactile way of sensing and opened towards the notions and linguistic disturbances that once again play a part in moving the space and the body into an unsettled and double-entendre situation.

|

| |

|

| | |

|

Drawing and writing

|

| |

|

This spatial displacement on the body’s premises is one of the constants in Martin Erik Andersen’s work. For this reason, it recurs with variations in the following work examples, where the material dialogue is carried over toward the areas of drawing and writing. This entails a shifting of attention that is directed inwards toward the textile’s entirely fundamental construction of interwoven threads. As I mentioned, a thread carries an etymological affinity with a drawn stroke that becomes alphabetical characters and eventually comes to fashion longer sentences across the surface of the paper. However, in the transition between thread and letter of the alphabet, another – and somewhat looser and more open to different meanings – kind of stroke situates itself, a stroke that has not yet determined whether it will place itself in the figurative/pictorial area or in the textual area.

|

| |

|

| | |

|

|

| |

|

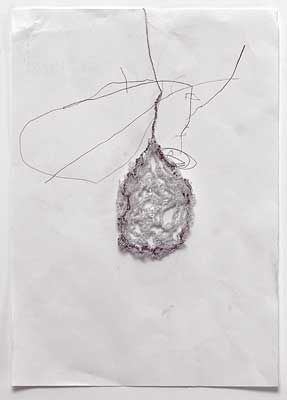

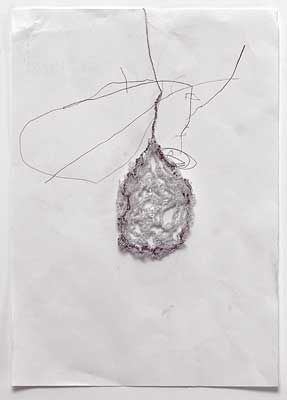

Paper Work (2005)

|

| |

|

| | |

|

One piece that conducts an inquiry into this threshold area is Papirarbejde [Paper Work] (2005), which, to put it succinctly, is a framed-in piece of paper with a semi-circular line drawing. From the top of the paper, a small and sensuously colored swatch of crochet-work is hanging down on a cord. The first associations that the work opens itself up to, perhaps, are thoughts related to the kindergarten, thoughts about finger-knittings and awkward children’s drawings that potentially maintain their power of fascination because the conventions related to drawing, such as scale and perspective, are not yet being complied with. Papirarbejde appears to be delving down toward the threshold where the material is merely being mastered precisely enough to put something down on paper or to make some kind of object. What happens in this space that is situated close to the reference point? The eye is struck first by a few essential differences between the pencil stroke and the thread as material phenomena. Both are documentations of tangible processes – of concrete effort. But whereas the stroke lies there on the paper as a definitive trail that can only be altered by erasing it or drawing over it with new strokes, the thread is decidedly more flexible. For example, it can be unraveled and crocheted in a new manner. On the other hand, the knitted object is dependent on all its threads if it is going to hang together. Should one of them be cut, the whole thing falls apart. On this background, we can apprehend the thread as a displaced translation of the drawn stroke, which nudges it over into a more mutable and more decorative but also a more fragile space.

|

|

|

|

| | |

|

In Hængelampe (one for loss, one for losing) [Hanging Lamp] (2007) the knitted fabric is placed in direct contact with letters and text. The sculpture can be described as a horizontally suspended lamp with words formed from bent neon tubes. Above the words, a knitting swatch of acrylic fiber is hanging; this piece of fabric could call to mind a heap of laundry that is drying on a rack. Fastened below the lamp, moreover, are a whole lot of small crotched objects that are hanging and dangling in the air. As a consequence of being detached from its original context, the neon text is very open. It appears to be revolving around the theme of loss and around losing or missing; in this light, it could invite a melancholic interpretation. Maybe, at the same time, it could be understood not only in a negative or melancholic sense but also more positively as a statement about loss (for example, loss of the self) as a possible prerequisite for being able to allow new things to enter in. Or, very likely, the sentence situates itself somewhere between these two poles in a kind of unconscious indeterminacy. One of the effects of the collocation of words and knitted fabric is that the sentence in itself comes to be perceived as a kind of knitting. This effect is manifest in an especially distinct way when you look at the lamp diagonally from the side, from where you cannot read the sentence, and thus the bent neon tubes are dissolved into arabesque-like abstract patterns, which furthermore intertwine themselves into the cables that give them their electric current. This change of attention also operates in the other direction, in the sense that you also start to decipher the actually knitted and crocheted elements as some kind of decipherable script, where you happen only to be missing the code in order to progress any further. Or is there a system in the way that the finger-knitting swatch is hung, at varying intervals? Is there a connection between the different sequences of color that the textiles display? A lamp is perhaps fundamentally an object that throws light on something, in this case, perhaps, primarily on itself. At the same time, the textiles continuously play their part in shielding off this illumination, in both a concrete and a metaphoric respect, with the result that the sculpture is always vanishing into itself. This leads us right back to the title, which perhaps, in the final analysis, points back to the loss of itself, which the work is.

|

| |

|

| | |

|

|

| |

|

Hanging Lamp (one for loss, one for losing) (2007)

|

| |

|

| | |

|

|

|

Ornamentation

|

| |

|

Several times already, I have been circling around ornamentation’s space, but without dealing directly with it. However, it could be said that the general preoccupation in the works with decoratively colored elements, for amusement parks and parties and for ornaments and pictorial references to, for example, the carnival, all points in toward the ornamental or the decorative, understood in the broad sense. In other words, in toward an area where it may not primarily be language and conceptions that stand in the center but rather a gaze that has been relocated halfway outside of itself as part of an absorbed sense-perception of sensationally colored electric light bulbs, weird music and arabesque patterns, which weave their way into and out from each other. Perhaps ornamentation can generally be described as a form or structure of thought where the goal-oriented, object-oriented and function-oriented attitudes are replaced by unbounded and fluid connections that inconclusively amalgamate themselves in every which way, a structure that sporadically becomes concentrated into motives and forms but which, at the same time, is always on the way somewhere else. Perhaps this ornamental space is also one of the privileged places where thought, emancipated from function, can turn into sensing structure, for example, into pattern or musicality.

|

| |

|

| | |

|

In Martin Erik Andersen’s work, the coupling of the ornamental/decorative with weaving and knitting attains its full scope especially in the use of ornamented Persian carpets. In Ucello Tombant (1995) the carpet-ornaments are simultaneously openly present and broken down into the work’s form. The sculpture consists of a spurious Wilson carpet, which has been cut into strips and hung from the ceiling in such a way that the rug’s front side and backside, by turns, intermesh into each other. Alongside the fragmentation, a series of transverse lines of nickel-plated steel has been inlaid into the material of the carpet. If these lines were to be placed parallel to each other, they would come to represent a so-called massochio, which is an early perspectival form invented by the painter, Paolo Ucello. Of course, discovering and figuring out all of these details in the work calls for a relatively long period of time, even though the title can function as a hint about the connections. Since the artwork’s space is being established between two essentially different optics, you could even say between an ornamental/decorative space and a perspective space, you could also inquire – in the very next moment – as to the deeper meaning. Well, in the first place, neither one of these spaces is privileged over the other; they are equally broken down and eradicated. This equal status inevitably leads, in the next going-over, to the possibility of envisioning them as being closer to each other. In the sculpture’s collapse, then, it becomes possible, momentarily, to perceive the perspective-like objective lines as detached ornamental strokes. Conversely, for their part, the ornamental strokes become partially transformed into the perspective drawing’s logical system. Both spaces are in possession of a visual and “rhetoric” aspect as well as of a logical and structural aspect, a state of affairs that the work does not predicate as a clear and distinct statement but maybe instead reviews and investigates and again causes to collapse.

|

| |

|

| | |

|

The piece, Ingen anden nåde end dette dit dørtrin [No Other Mercy than this Your Doorstep] (1998), also conjoins itself to the ornamental/decorative space. What transpires in this case is a material transference of the rug’s ornamental/decorative patterns to chipboard, upon which they are subsequently cut out with a marquetry saw. The carpet’s soft character and rounded organic patterns elicit a striking contrast effect in the chipboards’ hardness and angularity. The movement from a sensationally colored and visual space to the chipboards’ pale hue and porous structure, which can call the character of skin to mind, constitutes another displacement. But perhaps we should be looking for the primary meaning-related difference somewhere else, namely in the inversion that takes place when the carpet motive’s contours are stenciled into the wooden board, by means of which the thread is replaced by vacant space. This difference carries the wooden board’s ornamental space close to the threshold of absence. Principally, the artwork serves to outline a work-related dialogue with a previous weaver by imitating his original work. The resulting piece becomes all at once an amplification and an actualization of the already existing patterns. However, at the same time, it is instrumental in bringing about a paradoxical hollowing out. It could be said that ornamentation emerges into view at the very same moment that it vanishes again. In all the work examples that I have dealt with, there is a more or less open dialogue with the tradition, procured especially with the tangible physical exertions in matter as the intermediate link. What is extraordinary about this dialogue is that it reopens the historical space while, sometime in the next go-round, actualizing it as being concretely absent. The materials that remain point toward trails of that which is no longer to be found.

|

| |

|

| | |

|

|

| |

|

No Other Mercy than this Your Doorstep (1998)

|

| |

|

| | |

|

This situation, which is recapitulated in a variety of different leaps in Martin Erik Andersen’s sculptures, reminded me of the author, Bruno Schulz, and his textual world that is permeated with material conditions that always refer back to historical, social and symbolic spaces that are no longer to be found. What is so thought-provocative about Schulz, and perhaps also about Martin Erik Andersen’s work, is that the close-up focus on the material opens up a possibility for grounding oneself in the recently expired spaces on the premises of absence and emptiness. Absence, loss and effacement open both places up to renewed possibilities for presence and sensibility to the material world’s complexity and temporal disruption. Taking our marks in the material and the body, what can be established is an interchange between spaces that are otherwise essentially different. This contributes toward counteracting a reduction of the real to the agenda of the moment and a reduction of the material to pure functionality and fixed meaning. The defense of matter points toward a more fragile but also more coherent approach to the world. It makes it, to put it succinctly, possible to live.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

translated by Dan Marmorstein |

|

|

|

| | |

|

Stairway to Heaven - Highway to Hell

Interview

Magnus Thorø Clausen

Martin Erik Andersen

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| | |

|

MTC: The first thing I’d like to hear a bit more about is the white geometric block that has been placed in the beginning of the work. As you proceed further through the work, a number of more formless clumps (of the same material?) are placed on the floor. And when you arrive all the way at the other end of the elapse, behind one of the two upright carpets, you run into another geometric block. What’s the idea about starting and closing with these objects?

|

| |

|

| | |

|

MEA: The blocks are silicone pourings in cardboard boxes that originally contained some type of lighting equipment. I think of them as coagulations of some kind, composed of silicone, lights and transport. And it seemed natural to begin a closing of the work with the blocks. (The more formless clumps are wallpaper paste and paper, but actually I had also envisioned these in silicone, even if I eventually opted anyhow to make use of wallpaper paste in order to obtain a connection to the walls, where this stuff normally belongs.) The first silicone block you see in the exhibition is actually the last one that I poured. As a matter of fact, it was cast right in the museum. I’m fond of the idea that the last becomes the first, and vice versa. There’s always a transport involved in finishing a piece: I’ve got to find my way out of it and others (if they want to, that is) have to be able to come in. On many levels, the relationship between the fluid and that which has come to a standstill permeates the entire piece. Well, and the blocks, of course, constitute their very own space, a coupling to and a disengaging from a minimalist discourse.

|

| |

|

| | |

|

|

| |

|

| | |

|

MTC: From the silicone block, there’s some kind of road or pathway (of loose strands) of optic fibers and wires that move their way across the floor and wind up bifurcating into two complementary spaces. Along the way, the path occasionally comes to halt in certain small-sculptural situations. Can you say something about your choice of the path/filament as recurrent structure (and presumably symbol) in the work?

|

| |

|

| | |

|

MEA: Generally speaking, my own work with visual art (and all that surrounds it) is quite a ramified and fluidly transient terrain of experiences, meanings, materials, connections, choices, cul-de-sacs and maybe even pathways. A loose path represents one of many possible avenues for the body to get from one place to another. A path is a kind of potential movement, shared in common, which can be followed or forsaken. This particular path is, of course, a kind of meta-path. Certainly, you will not walk on it. Instead, you’ll walk alongside it. And then again, it is supposedly also a closing in itself, which establishes space around itself through the agency of its own light. The path here, I would say, is an image. In this respect, it is heavily laden with symbolism, but its construction also pulls in another direction by virtue of its manner of bearing its own micro-pragmatics as an intermediate stadium between wire, filament, needlework, drawing and interior illumination. The path amalgamates light, wires, crochet work and movement. What bring the momentum to a standstill, of course, are the small mirrors, among other things. These crease and snap the path. In the work, once again, as we’ve observed before when we spoke about the boxes, there is the unresolved relation between flowing and coagulating. Of course, the path is similarly bound up with both aspects of the exhibition’s title, the highway to hell and stairway to heaven. The body, I suppose, always constitutes a cross between vertical and horizontal. A flat horizontal path positions the body horizontally in the space. Its very flatness activates the act of standing and walking. And maybe the path and the blocks in this work actually fashion a kind of pervasive socle for the two complementary spaces. The first block’s size, moreover, is very close to that of the standard foot, just about [European shoe] size 43. And the relationship between sock and socle is, naturally, always vital.

|

|

|

|

| | |

|

MTC: In the two rooms at the end of the path, certain ”translations” made of an ornamental carpet in fluorescent silicone are set up. Can you tell us something about the thoughts behind your manner of preparing the carpet and about the space you’ve established around this element? Why have you chosen to transfer it and cut it out in silicone?

|

|

|

|

| | |

|

MEA: As a matter of fact, silicone is essentially a translation material. This is a certain kind of silicone that is ordinarily used for rubber molds and for pouring casts. The ornamentation is first cut from Styrofoam, which is subsequently modeled in silicone and finally cast, in positive once again, in silicone. The ornamentation from the carpet prototype has been drawn by cutting away the contour, which means to say that the line itself has been cut away. The silicone is also in possession of the translational quality that it is translucent. Visually, it is half present and half gone, in any event, in relation to the interior lighting. The translucency tints it as if it were in between. Just as the path is not a path, neither is the carpet a carpet. The music comes from Central Asia, from the same geographic region as the carpet prototype. The sound is a digital re-recording from a vinyl single. In the translation from vinyl single to Mp3-file, the noise from the pick-up (from a record player that is not there) emerges as a kind of parallel to the silicone’s distortion of the carpet. What arises is an interval in the transport. Iron rods and knitted swatches are conceived as some kind of loose transitions between lamp supports, bodies, architecture and sculpture. And as provisional cursors that chronicle certain specific spatial dimensions in the gap between carpet and body.

|

| |

|

| | |

|

|

| |

|

| | |

|

MTC: Personally, I feel that the carpet plays a part in introducing a particular cultural space that exists behind our everyday lives and maybe also behind modern Occidental space. This space is connected to a prehistoric nomadic culture with a radically different scheme of things, where the boundary between physics and metaphysics is also perhaps more vague and fluid. The garden iconography in the carpet, for example, might point both toward the tangible ground and toward heaven’s imaginary harmony. This archaic world is then being filtered through a fragile and, materially speaking, more contemporary reality of colored lamps and proto-architecture. In this connection, would you say that what’s happening in this work is also a transport between past and present, between metaphysics, architecture and the abandoned amusement park?

| | |

|

| | |

|

MEA: To be sure, transport and time are closely connected. Without time, everything would stand still and if nothing were moving we would hardly be able to see time pass. When I declare that I am interested in translation and transport, I am referring specifically to an interest that I cannot establish without having something that has to be displaced, eliciting something else than what I already have. And a Turkmen nomad’s carpet from a culture that the Russians obliterated in 1881 is indeed a tangible and concretely cultural object that did not come from Mars but nonetheless represents a colossal foreignness. There isn’t anybody who really knows what the iconography on the carpets actually means. The main pattern, however, is known as a ”Gull”- It appears that this could be a word for ”flower” that was borrowed from the Persian language. However, in the Turkmen language, ”Gull” simply means ”pattern”. For my own part, I believe that the pattern, as such, can be traced all the way back in an uninterrupted trajectory to the cave dwellers. The ornamental is presumably a fluid and transitory space, where people existing in – and moving around every which way through – all different times and places are conversing structurally with each other. This is interesting to me, yes, but as I come to ponder over it, it doesn’t really interest me – because it’s all too generalized. The noise, the mistakes, the driveling nonsense and the specific are that which cause reality to surge along in defiance of our attempts to envelop and embrace it. What I’m trying to do is, I guess, to delimit a kind of local open order that can sustain its own collapse, that is to say, an obviously erroneous translation that eventually turns into a language of its own. The abandoned amusement park is most decidedly a site for this kind of order. And I have no trouble believing that things become metaphysical as soon as we abandon them.

| | |

|

| | |

|

|

| |

|

| | |

|

MTC: As I was busy looking at the translated carpets, I came to think that what lay before me could also trigger associations with closed doors or gates. Proceeding from the two poles designated in the title, heaven and hell, it might be relevant to point to a[mtc1] few other closed gates that have appeared in the history of sculpture, such as Ghiberti’s The Gates of Paradise (1425-1455) or, naturally, Rodin’s The Gates of Hell (which was never finished) and moving even further out, Duchamp’s The Large Glass (1915-1923), which opens translucently into a super-rational space. Or, what might be more obvious, Robert Morris’ bronze gates from the 1980s. Whereas the first two examples and possibly also the latter example refer unequivocally to heaven or hell, your carpets, I would say, are more polysemantic. How do you respond to looking at the situation in this way? Is it too far out for you?

| | |

|

| | |

|

MEA: It’s definitely fair enough to think about doors. Doors, or course, are transitions between rooms. Arrested movement . . . transport coming to a standstill . . . smack dab in the middle of differences. And actually, it’s not only the silicone carpets that can be considered in this vein. In fact, my project as a whole is conceived with these things in mind. Also when it comes to many of the details; for example, the give-away print on display here, which you’ve got to leaf through should you want to be capable of deciphering its content. Furthermore, there’s actually a Turkmen carpet format that is called ”engsi”. Up until the middle of the twentieth century, this small rug was sold by carpet dealers as a prayer mat, but it was never used for such purposes originally. It has always been utilized as the doorway into the yurt, the Turkmen tent. The engsi’s iconography is religious, indeed, but it is pre-Islamic. At this time, I’m also working on a replica of the Persian Ardabil carpet that has an inscription by Hafez woven into its surface that says, among other things, ”No other mercy than this your doorstep.” Maybe the door is always a prayer for mercy. The form of visual art that I’m working with is possibly built up around doors that are destruction, on the one hand, and ecstasy, on the other: carousel doors, perhaps.

Doors, gates and transitions, of course, have historically always been impetuously ornamented. Surely, in part, as a type of control of the fear of the stranger and partly also as an unfurling of ecstasy in the face of what is demarcated. Maybe there is an awful connection between Loos’s ”Ornament and Crime” and Kafka’s inconsolable doorkeepers. Modernity and rationality are merciless threshold watchmen that will dispatch you from one emptiness to the next. Artistically, I just don’t feel like facing emptiness anymore. I don’t think that there’s time for doing that. I prefer ecstasy and garbage and maybe that’s why I’m not so frightened anymore of flinging clichés and flowery rhetoric like heaven and hell all around me, even though there may well be somebody who, quite rightly, will find this to be double empty!

| | |

|

| | |

|

MTC: One of what is perhaps the most noticeable structures that permeates the entire exhibition is the transport between darkness and light (in different colored nuances [mtc2]), which in a number of different ways dissolves and puts the work’s elements into motion as shadows on the walls and the floors. Can you say something about working with the light and its potential relation to the scenographic?

| | |

|

| | |

|

MEA: Well, I certainly do not feel that scenography has any patent on colored lights. The amusement park, the discotheque, the party and I imagine even church windows were there before. And the notion about the installation work being intrinsically related to theater is something I’m really opposed to, probably because it reduces all objects and spatial relations to subordinate props: stage requisites in a theater where I’m then supposed to be the director and the members of the visiting public are supposed to be the actors. What I’m working with has just as much – or just as little – to do with theater as it has to do with selling carpets.

As opposed to a neutral interior illumination, colored lights have the characteristic attribute that the shadows are transformed into complementary colors, which are roughly of equal intensity. Red lights cast green shadows and green lights cast red shadows. And maybe what I’m aiming at, in terms of the light and in terms of the color, is precisely a transition between light and darkness. Maybe I’m trying to conjure up a place where all the colors are mingled[m3], a little like what we know from the clouds at dusk . . . a kind of chromatic interspace.

And then of course, there’s the fact that the work makes itself independent from the place or else it takes over the room when it carries its own light with it. Maybe the work exposes the place with its own optics, instead of the other way around.

| | |

|

| | |

|

|

| |

|

| | |

|

MTC: I would like to end with a question directed at the personal space. Considering the movement in your work-production from the close of the 1980s until now (some examples of which have been included in the present exhibition and presented in a room of their own) it appears that there are two overlapping courses: the one moving out toward an increasingly more inclusive assimilation of heterogeneous materials and meanings from widely divergent places and times, the other moving toward an increasingly more open employment of the personal – from the biographical (as we see here, for example, with the give-away print) to the workshop piece (for example, the silicone block that we started with). Do you agree that what we have here is a progressive development or has the span, as such, always been there? What significance does the personal have, in general, in your approach to making art?

| | |

|

| | |

|

MEA: As far as I’m concerned, the span, in itself, has been the same. It’s more a question that the grid has expanded, because there is always some kind of building activity going on around it. New points are emerging, which alter both whatever you’ve made before and whatever you’re going to be creating hereafter. Maybe the internal gaps in the span are getting smaller and maybe some of the disparities are gliding together more smoothly. Perhaps the whole complex is becoming more inclusive because it’s getting more nuanced and subtly balanced. Minor differences are coming to be better ensnared in a fine-meshed net. I feel fine about all this because basically I know that it’s a very loose construction, which will cave in when only a few centimeters are missing in the precision.

When it comes to the personal, well, I’ve always been a part of the fringe of whatever grid within which I happen to be working. Actually, I’ve always regarded the personal aspect as material that necessarily must be used as that which it really is. That my own biography, though, might seem to be a little extra obscure is just my own condition. That’s the way it is. If the personal is a material on a par with other materials, then I only have myself to hurl onto that ball field. On the other hand, I have been trying to do this structurally, so that it will take on some kind of general character as a sign for the personal. It must not become too locally concerned with – and too locally designed for – me and mine. Anyway, that’s the kind of thing that the dirty tabloids are so much more adept at wielding.

| | |

|

| | |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

translated by Dan Marmorstein |

|

|

|

download PDF version |

|

|

|

| | |

|

| | |

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|